Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

The Budget combines $10 billion of increased spending over the next year with the pre-announced Stage 3 tax cuts, and yet projects a sharp fall in inflation over the next 12 months. How does it achieve this seemingly magical combination?

The cost-of-living subsidies and relief measures will reduce measured inflation. But they add to household incomes, particularly of households that will spend a large share of that additional income, and so will contribute to at least some extra spending. And temporary cost-of-living relief measures simply move inflation, pushing it to later years, stretching out the inflation problem. The RBA frequently notes that it ‘looks through’ temporary supply-driven inflation shocks, and by that logic it should not be fooled by temporarily lower measured inflation. The inflation dragon still lurks in our future.

If anything, the Budget adds to, rather than reducing, the excess of demand relative to supply in the economy which is driving persistent inflation and is of concern to the RBA. It’s not clear that the RBA can respond to lower measured inflation with lower interest rates when the underlying demand-supply imbalance remains.

The positive interpretation of the Budget is that by reducing near-term inflation it lessens the chance of rising inflation expectations, and so ingrained strong wage growth and effective indexing of prices, which would make eliminating inflation harder. It’s unlikely this effect is large enough to dominate.

By reducing measured inflation, the Budget is clearly designed to take the pressure off interest rates. The key question is: will it achieve that? I’m sceptical.

Key numbers in the Budget:

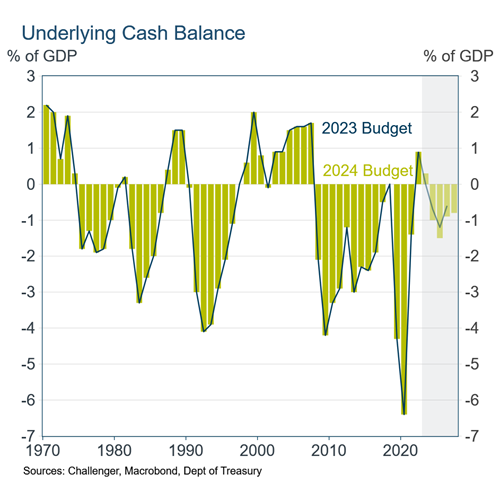

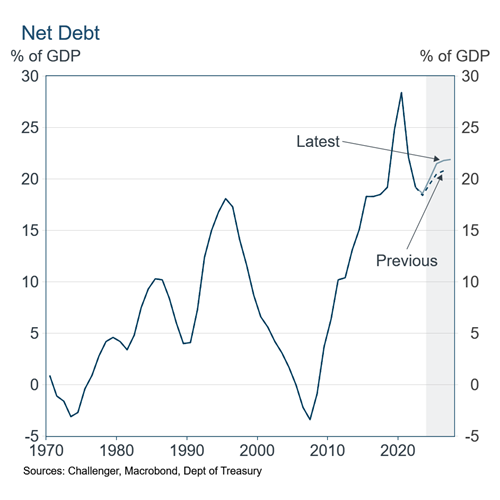

- The underlying cash surplus for the fiscal year 2023-24 is projected to be $9.3 billion, 0.4% of GDP, following a surplus of $22 billion in 2022-23.

- These are the first budget surpluses since the string of six years in the leadup to the Global Financial Crisis that tipped the budget into the red in 2008. The past two years have benefited from high commodity prices.

- But as the fall in commodity prices and the stage three tax cuts reduce revenue growth, and expenditure increases, the budget is forecast to again return to deficits from next year (averaging $30 billion, 1% of GDP, per year over the next four years).

Key spending in the Budget:

- There is a big focus on ‘cost-of-living’ with $8 billion of measures, including: $300 energy rebate for all households, 10% increase in rent assistance, medicines co-payment frozen for 1 year (5 years for pensioners and concession card holders).

- There were some, but incomplete, details on the Government’s ‘Future Made in Australia’ policy which will cost $22.7 billion but spread out over a decade (focused on critical minerals, hydrogen).

Economic forecasts:

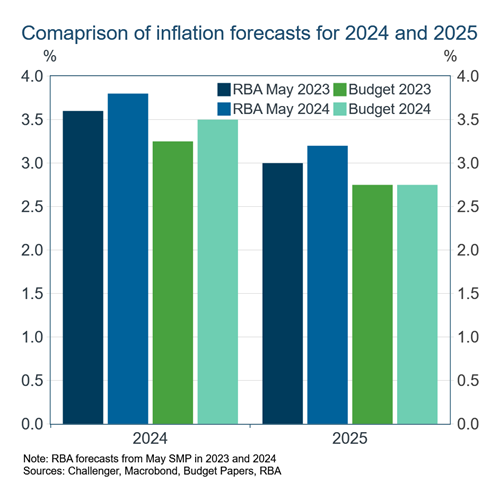

- The Budget recognises that inflation for calendar year 2024 will be higher than projected a year ago, by 0.25% points to 3.5% (similar to the upward revision in RBA forecasts). But the Budget forecasts inflation over 2025 to be 0.75% points lower than the RBA forecasts, at 2.75%.

- The Government’s narrative is that the cost-of-living measures in the Budget (energy subsidies and rent assistance) reduce inflation by up to 0.75% points.

- Unemployment is forecast to peak at 4.5% by mid 2025 (0.2%pt higher than the RBA), with wages growth slowing sharply 3.25% over the next year (from the current 4.2%). GDP growth picks up only very gradually by 0.25% per year to be 2.5% by 2026-27.

These views do not take into account anyone's objectives, financial situation or needs. It is important to consider these matters before making any investment decision. It is general information only and is intended solely for licensed financial advisers or authorised representatives of licensed financial advisers, and is provided to them on a confidential basis. This article and the information in this article must not be distributed, delivered, disclosed or otherwise disseminated to any investor, without our express prior approval. Any examples shown in the article are for illustrative purposes only and are not a prediction or guarantee of any particular outcome. This article may include statements of opinion, forward looking statements, forecasts or predictions based on current expectations about future events and results. Actual results may be materially different from those shown. This is because outcomes reflect the assumptions made and may be affected by known or unknown risks and uncertainties that are not able to be presently identified. To the maximum extent permissible under law, neither Challenger nor its related entities, nor any of their directors, employees or agents, accept any liability for any loss or damage in connection with the use of or reliance on all or part of, or any omission inadequacy or inaccuracy in, the information in this article.

Related content

Protecting retirement income from inflation